Minimums

My head is beginning the switch to go-around mode. I glance up at 100 above, and see nothing. No difference from 1000 above. If I don't see something soon . . .

Minimums. No contact. My hand is on the throttle, my eyes on the PFD. My wife says, I see lights. On the ground.

I glance up again, just for a peek. Two red runway end lights, just where they should be.

“I'm going back in.”

Earlier

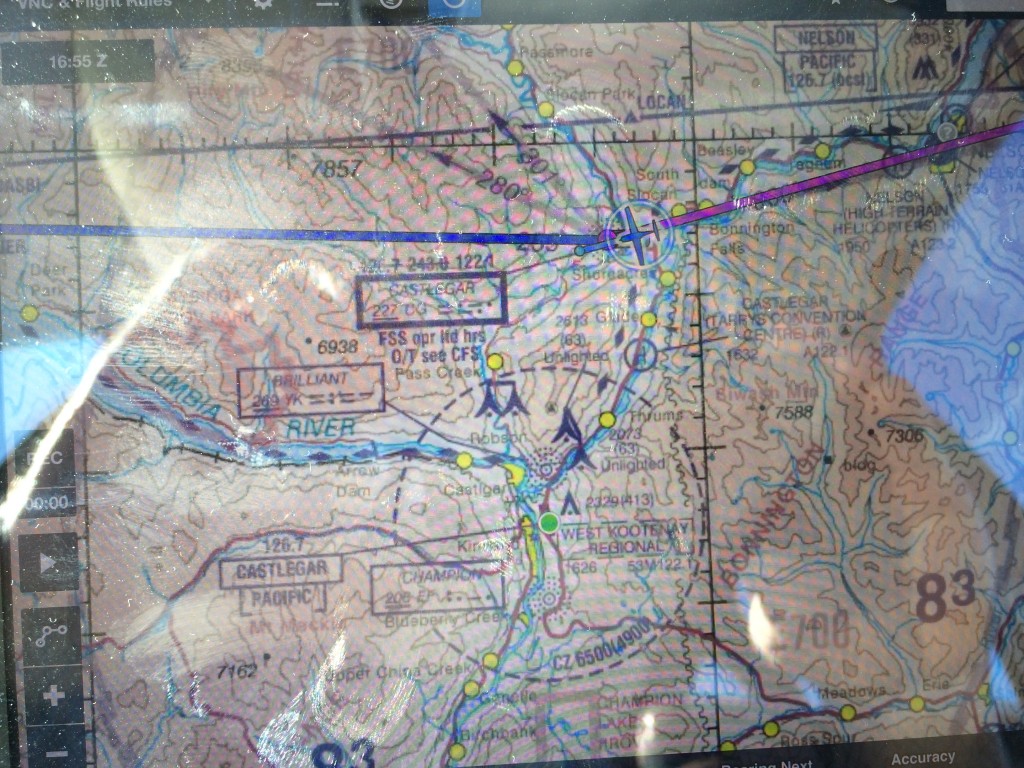

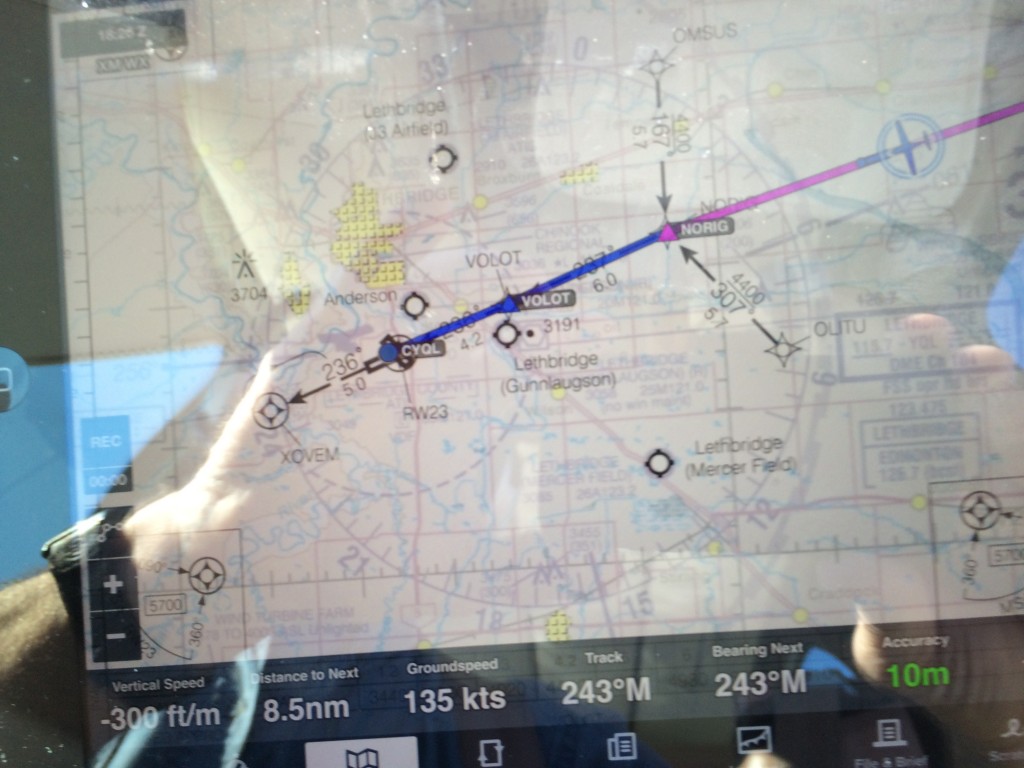

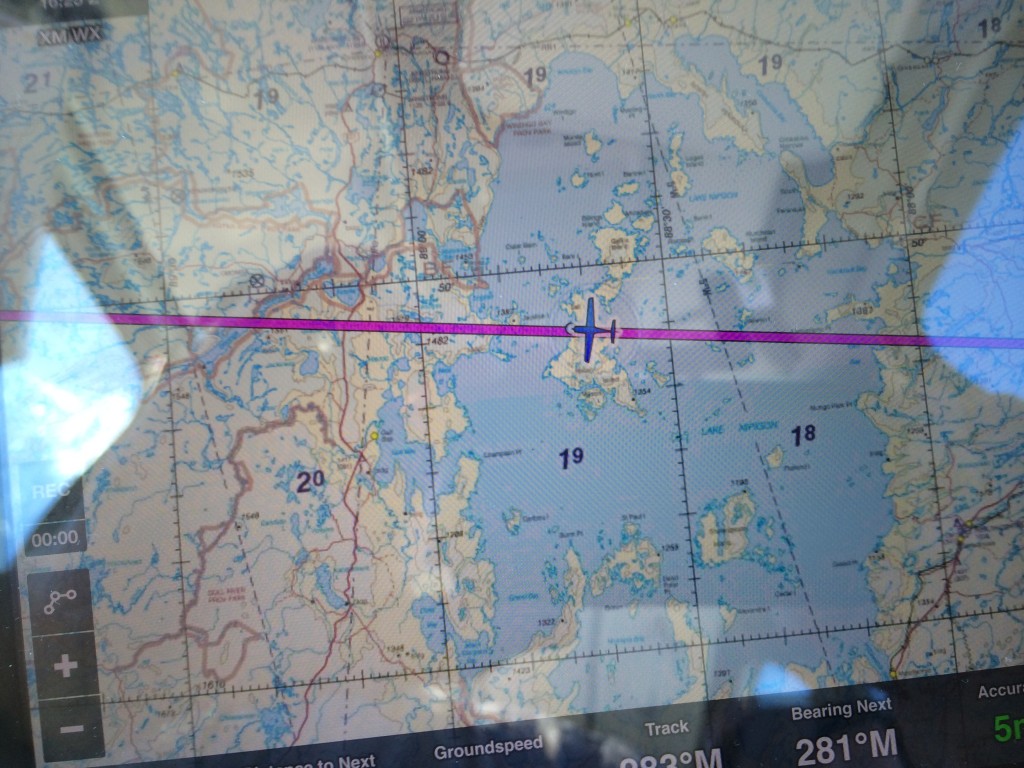

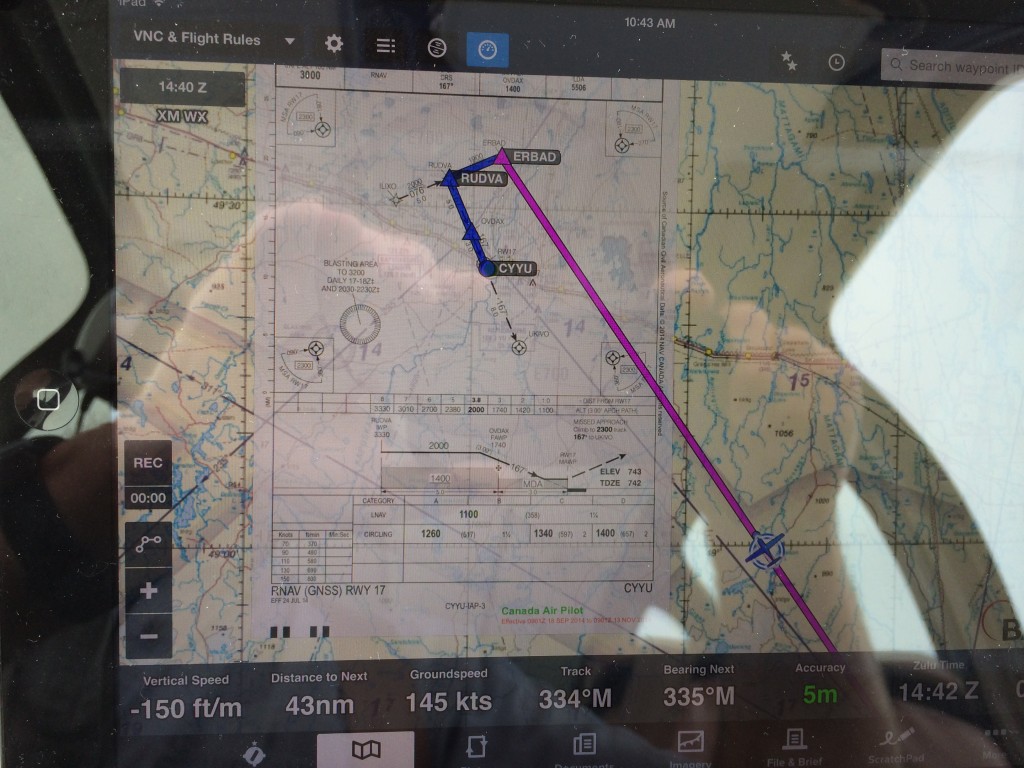

The METARS for Champaign, IL (KCMI), our destination, have been between 200 and 500 overcast most of the day. KCMI has been a red dot (low IFR) on my iPad (I'm using the ForeFlight app), but near KCMI, in Indiana and Ohio, are numerous blue (marginal VFR) and even a few green (VFR) dots. The air mass below 10,000 feet is warm. It is +8°C on the ground and +5°C here at 8000 feet. But that warm air has been moving in over cold ground, a recipe for fog. All day we have been cruising in the clear over a solid undercast. Here is the scene as we approach Top Of Descent: The setting sun is not helping the weather: the new ATIS (Automatic Terminal Information Service) gives the wind as 160° at 11 knots and the ceiling/visibility as 200 feet and 3/4 mile. The RVR (Runway Visual Range) on runway 32R is 5000 varying to 6000 feet. The approaches in use (in theory) are 14L and 22.

The setting sun is not helping the weather: the new ATIS (Automatic Terminal Information Service) gives the wind as 160° at 11 knots and the ceiling/visibility as 200 feet and 3/4 mile. The RVR (Runway Visual Range) on runway 32R is 5000 varying to 6000 feet. The approaches in use (in theory) are 14L and 22.

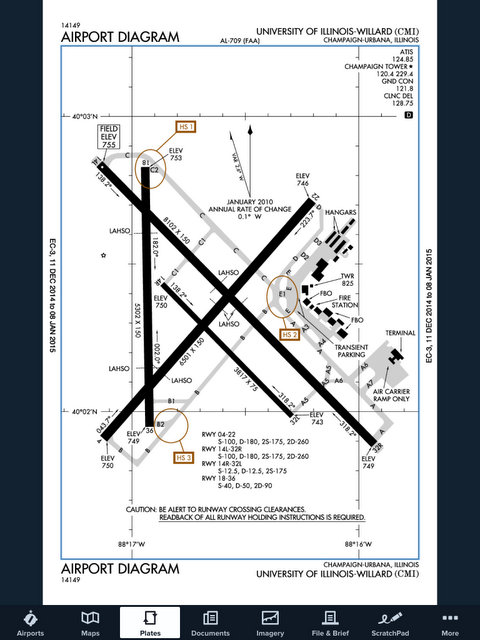

For reference, here is the airport diagram:

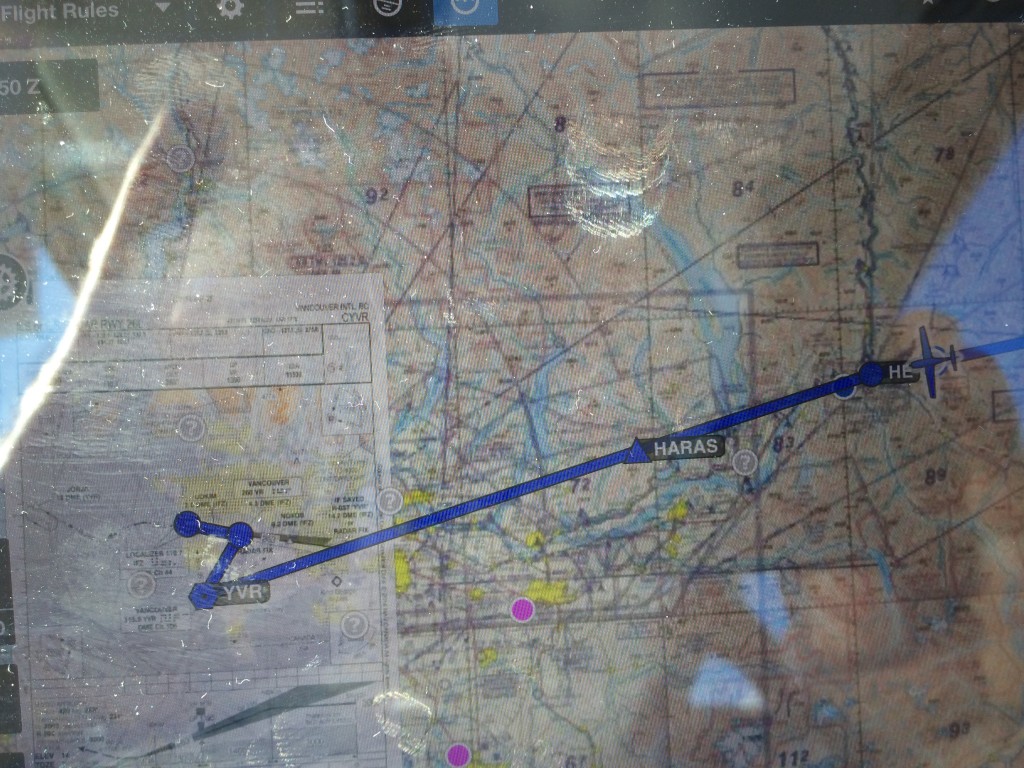

During the last hour Terre Haute, IN (KHUF) has emerged as the new, practical alternate. Now it's time to finalize the approach and missed approach plans before things get busy.

During the last hour Terre Haute, IN (KHUF) has emerged as the new, practical alternate. Now it's time to finalize the approach and missed approach plans before things get busy.

At 8000 feet the wind is strong out of the south-southwest, backing around to 160/11 on the surface. My plan is to do the GPS LPV to runway 14L, and then if I can't see enough to land, do an ILS to the other end, 32R. That would have the advantage MALSR (approach lights) and PAPI (visual approach slope lights), which would make the transition to visual flight a lot easier.

Here we go. I check in with Champaign approach with the ATIS. She says cheerfully, what would you like? I request direct ORANJ for the LPV 14L approach. I pronounce it like the French word, with the accent on the second syllable. That's my take on the J. Sure, she says. Cleared direct orange and cleared for the RNAV 14L approach.

A digression is in order here. My first introduction to glass in the cockpit was the B-767, which I flew in the early 1980's as a First Officer. Boeing's philosophy was to make a track up display, which had the advantage of making an IFR approach easy. Fly the airplane so the track arrow on the HSI (Horizontal Situation Indicator) points up. But what about heading? In the Boeing, as I recall, there was a pointed tuque (triangle atop a square) which represented heading, and was of course, like the airplane, sitting off to one side in a crosswind.

A digression is in order here. My first introduction to glass in the cockpit was the B-767, which I flew in the early 1980's as a First Officer. Boeing's philosophy was to make a track up display, which had the advantage of making an IFR approach easy. Fly the airplane so the track arrow on the HSI (Horizontal Situation Indicator) points up. But what about heading? In the Boeing, as I recall, there was a pointed tuque (triangle atop a square) which represented heading, and was of course, like the airplane, sitting off to one side in a crosswind.

It seemed wrong to me. Heading is where the airplane is pointing, which is where I am pointing if I'm sitting straight in my seat. So I was pleasantly surprised when I transitioned to my next glass airplane, the A-320, in 1995. The Airbus has heading up displays. And (I suppose just because that's the way my head is wired) I found it even easier to fly than the B-767. I remember, In my first year on the airplane, being cleared while on downwind for an ILS 18 at Val D'Or, Quebec. Instead of a full approach with procedure turn (there is no radar up there – or least there wasn't in 1995), I vectored myself onto an intercept like a controller with radar would have done.

Nothing is perfect. The Airbus is so highly automated, its fly-by-wire so distant from normal airplane feedback (no trim feel), that I was, I later realized, losing skills as I vectored myself for that approach using the heading bug.

Today I am going to need all the skills I can muster. True, I have been working hard for more than two years to regain what I once had. And I have had expert help: Andrew Boyd at Smiths Falls, Ontario. But I am seventy years old and tonight I am tired. This is the third leg today, and I have been airborne six and a half hours. The Bonanza does not have an autopilot, so all the flying, including an ILS at Albany, NY and an RNAV LNAV+V at Marion, OH, has been by hand. In deciding whether to even try the approach, the airplane and equipment and regulatory limitations fade in importance. My own limitations have moved into first place.

But I have good equipment and I am thoroughly used to it. Here is my Primary Flight Display, an Aspen 1000 Pro.

As soon as we pass the RRRED intersection (The Initial Approach Fix; head of the “T” on the chart) the localizer and glide slope scales will appear on the top half of the display. These are the green diamonds you see above. My tired eyes, doing their instrument scan ever more rapidly as we move down the narrowing cone of the approach toward the runway, won't have to move very far. The display is more or less the size you see above, so within and inch of the tip of the airplane symbol (attitude) I have localizer, glideslope, airspeed, and altitude. Just below the localizer scale is a data space with TAS (true airspeed) GS (groundspeed) and wind (148°/16 kt on the display above). But there is a more important piece of information, arguably one of the most important: track.

As soon as we pass the RRRED intersection (The Initial Approach Fix; head of the “T” on the chart) the localizer and glide slope scales will appear on the top half of the display. These are the green diamonds you see above. My tired eyes, doing their instrument scan ever more rapidly as we move down the narrowing cone of the approach toward the runway, won't have to move very far. The display is more or less the size you see above, so within and inch of the tip of the airplane symbol (attitude) I have localizer, glideslope, airspeed, and altitude. Just below the localizer scale is a data space with TAS (true airspeed) GS (groundspeed) and wind (148°/16 kt on the display above). But there is a more important piece of information, arguably one of the most important: track.

In the old days we flew a precision approach by guesswork: we flew a heading and a rate of descent and noted, over time, what happened. If the localizer and glideslope stayed centred, we had made good guesses. But if, for example, the loc indicator (needle or diamond) has moved right of center, it means we have drifted left off the centerline. What we do not do is turn right until the needle centres again. That was the technique Bill B. used in his Tri-Pacer down in New Jersey in 1969. I remember him saying, that loc needle was like a #$%# windshield wiper!

No. What we are doing in our heads is say, that 155° heading was not enough. We have a crosswind from the right. We'll turn right to 165° to re-intercept, then turn back to 160° and see what that does. Our heads are remembering the effect over time of various headings, and deducing what heading it will take to track the localizer. We do the same with the glideslope, deducing what rate of descent it will take to keep the needle centred. As we get close to minimums, down at the pointy end of the cone of the approach, those heading changes will be two degrees or less, and any deviation will have to be corrected more quickly. In effect our brains are doing Calculus: noting change over time and rate of change, differentiating. That is a lot of work. A lot of intense, hard, rapid work. I'm not sure I'm up to it tonight.

But wait: I don't have to. Move your eyes down another inch on the display. Just below the heading (163°) is the green tip of the track arrow, representing the on-course line of the approach.

If you look carefully, you can see a small aqua diamond superimposed on the arrowhead. That's where it is supposed to be, because the diamond is the aircraft's track, the track made good over the ground, even though the airplane is flying a heading through the air and being blown sideways by the wind.

Where does this information come from? The GPS. The GPS is computing position about once per second. Then it uses the Calculus, that great mathematical technique invented by Newton and Leibniz, to differentiate the series of positions (dS/dt) and calculate velocity, a vector, which has both speed and direction. These are displayed on the Aspen PFD as groundspeed (GS) and track (where the diamond is on the compass rose).

Having track was what made the B-767 and the A-320 easy to fly on instruments. A computer is doing the calculation you would otherwise have to do continuously in your head. And the Aspen has my favourite, the heading up display. So my scan now goes something like this:

- Attitude? Correct if not on target. Now, bypass loc and glideslope, because they will still be where they were two seconds ago – centred.

- Track Diamond? Is it on the tip of the track arrow? If not, turn immediately to put it back on.

- Note heading on the way back up. That's the heading that works, at least for the moment.

- Loc and Glideslope still centred? Whew. Caught that one in time.

What is the logic here? First you have to be on the localizer. Then, you have to steer so that the aircraft track made good (the diamond) is the same as the localizer track (the green arrow). That way what's good will stay good, because two seconds or ten seconds from now the aircraft will have moved along the localizer, not drifted off. The Track will be the same as the Desired Track.

That is the centre of the scan, the part repeated every cycle, a second or two apart as you get near minimums. With that diamond where it is supposed to be you can add another parameter or two to each cycle of the scan: airspeed, altitude, glideslope trend.

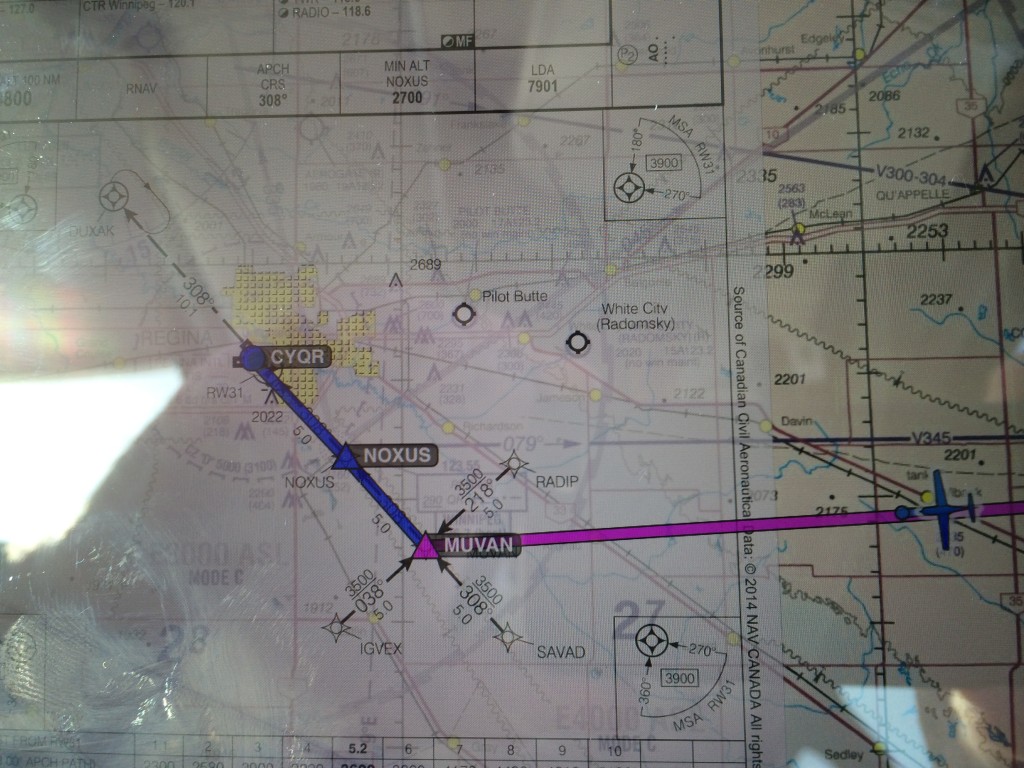

Now my talking to myself will perhaps make some sense. I have briefed the approach and the missed approach, speaking aloud both to keep myself focused and to keep my wife (not a pilot but a tremendous help) in the loop. We have passed ORANJ.

OK, we're slow here on base leg. A direct headwind and almost forty knots. Yeah, we're in cloud already. Hardly noticed. Get that landing light off. And the strobe, too. Go dark. Temp's good: +8°C. Diamond on the needle. Seventeen inches. Hold 3000 and intercept from there. Got gear speed. A little slower: sixteen inches. Wind's starting to back: 200/35. Diamond on the needle. (I don't know why I called it the needle instead of the arrow, but I did).

“Bonanza Quebec Romeo Victor, contact tower one two zero dezimal four.”

“Quebec Romeo Victor, 120.4. See ya.”

Switch freqs. Leave Approach in the standby for the miss. Diamond on the needle. Level three. Two from RRRED.

“Champaign Tower, Bonanza Charlie Foxtrot Quebec Romeo Victor on the RNAV 14L.”

“Quebec Romeo Victor, cleared to land runway one four left.”

That's it. Now work. Should be under the slope at three at RRRED. Diamond on the needle. Watch for the turn alert on the Garmin. There it is: 8 seconds. Won't get the slope 'till we pass. Speed's slow enough: catch it. Eighteen inches. Diamond on the needle. 2 seconds. Turn left to 135° NOW. Not too fast. Diamond to 135°, not heading. Steady. OK, to waypoint now GRANJ. That's the FAF. And there's the loc and glideslope scales. Diamond on the needle. Heading 155°. Glideslope alive. Stand by for the gear. Diamond on the needle. Diamond keeps drifting left. More right rudder. Remember, 155° heading works.

OK, gear down. Trim. Fifteen inches should work. Diamond on the needle, 155°. Sagging under. Sixteen and a half inches. Want 90 knots and 300-400 feet per minute. Green light and down on the tape. Glideslope's good. Try sixteen inches. Diamond on the needle. GUMP check. Gas, right tank. Diamond on the needle. Trim and power good. Holding the slope. Undercarriage: green and tape. Diamond on the needle. Mixture rich. Prop fine. Here comes GRANJ. 2700. Missed Approach 2600, set. Diamond on the needle. Wind's backing some more. 180/34. Diamond on the needle. Still need 155° heading. Trim and speed good. Attitude's plus 2 1/2°. Not going to see much tonight at that attitude. Flap 10°. Trim. Diamond on the needle. That's better: attitude zero. One thousand to go.

I say that passing 2000 feet MSL. In the briefing I have rehearsed what minimums will look like on the old round altimeter as well as putting the number, 960, into the MIN window on the Aspen. 960 is 1000, the top of the dial, twelve o'clock. Here at 2000 we're a thousand above. My work now is to keep the airplane in the cone, to make this approach as accurate as possible, because there will be no room for any maneuvering at all at minimums. It will be right on or go around.

I am working really hard, and I almost feel physical pain when I look down and see that tiny diamond has moved. I haul it back quick with sharp, ten-degree bank turns that last for a second or two. I probably should be steering with my feet, but I haven't practiced that and now is not the time. I am sweating.

Diamond on the needle. Wind 180/30. Heading maybe 154°. Ground wind's 160/11. Watch for the change. Five hundred to go. Diamond on the needle. Changing now. Heading 152°. Speed's good. Gonna have to taper off the power a bit after we lose the wind. Diamond on the needle. Follow the change. Wind 180/25. Good, the change is not too abrupt. Diamond on the needle. Assess: loc and slope good. Speed's up a bit, fifteen inches and that'll be it. Diamond on the needle. A hundred above. Sneak a peek. Nothing. Just like a thousand above. Hand on the throttle. You'll have to pin 10° nose-up on the missed approach. That's gonna take a good push at full power. Diamond on the needle. Hang on. Heading 150°.

I hear the tiny ping from the Aspen as we arrive at minimums. Insulated by the noise-cancelling headset, it seems like it is coming from another planet. In my peripheral vision, there is nothing. Not even a glow. My wife says,

“I see lights! On the ground!”

I look up. There are two fuzzy runway end lights, right where they should be.

“I'm going back in.”

What I mean is that my eyes are going back in, to the Primary Flight Display. When I glanced outside, I saw enough to know that the runway environment was where it should be, but also to know for sure that I would have no cues about height and very little about alignment if my eyes stayed outside. In my 500 millisecond glance the red lights were blurry. Sure, my wife had seen lights on the ground, but that is looking more or less straight down. My red runway end lights were ahead, farther away because of the slant range. And the runway itself, even further away and at a shallower angle, was invisible. That means there is no ceiling as such, merely a vertical visibility.

But the METAR had been between 1/2 mile and 3/4 mile visibility all afternoon, and the ATIS and the tower were saying 3/4 mile. Best of all, the RVR (admittedly on the far end of the runway, near the touchdown zone for 32R) was 6000 feet. So at ground level, at the far end of the runway, the visibility is more than a mile.

I decide to fly it down to 100 feet, if I can keep it locked on the localizer and glideslope. I know these are not radio aids, locally transmitting on VHF and UHF like real, legacy localizers and glideslopes. Instead they are calculated from a series of positions relative to the runway in three dimensions. But the worst case accuracy for a WAAS GPS is a spherical error of 7.6 meters (25 feet), and the demonstrated accuracy (by the NTSB) is 1.3 meters (4 feet). So with this GPS localizer and glideslope nailed, I have no worries about not landing on the runway.

Diamond on the needle. Pull slightly to correct that sag. Wings level. Diamond on the needle. Heading 145°.

I look out again. Rows of runway lights. I don't remember how many. The visibility is better. Not much better, but better. The runway centreline paint is now visible. I hold attitude and wind off the power, using the vernier control. One of my better landings, God knows why.

“Bonanza Quebec Romeo Victor, um, are you down? We can't see you.”

“Yeah, we're rolling out.”

We are down to taxi speed and passing the C1. The visibility is better at ground level. I switch on the upper landing light.

“Oh, now we have you, Quebec Romeo Victor. Cleared across 22 and into the ramp via Bravo. Stay with me.”

History, Rules, and Politics (not to mention the Bottom Line)

The girl behind the desk at FlightStar, the FBO, tells my wife we are the only airplane that has landed at Champaign since she started her shift at 2PM. (We landed just before six.) Our son picks us up, and he also has to pick up a colleague flying in from Chicago. We hang around the main terminal for awhile. The flight winds up cancelling. I begin to wonder if I should feel bad for landing.

I recently read a brief history of low visibility approach techniques. It was by Jack Desmarais in Position Report, the journal of RAPCAN, the retired airline pilots of Canada. I don't have it here so I'll summarize as best I can.

The military developed techniques such as the PMA (Pilot-Monitored Approach), where one pilot flew the approach and go-around on instruments, and the other pilot stayed heads up and took control and landed the aircraft if he had sufficient visual references. This system had the advantage that neither pilot had to transition, to go from instrument to visual flight. Successful approaches were made even in zero-zero conditions, especially after the development of heads up systems, where flight path information was projected onto the windshield, so the pilots' eyes did not have to move.

But the airlines and the manufacturers moved in a different direction: to autoflight and autoland. Dual and triple-redundant autopilot systems and radar altimeters enabled a progression from CAT II (100 feet) to CAT III (autoland). Of course there were limitations: RVR (visibility), wind (not too strong) and equipment (everything had to be working.) There were approach bans (can't go beyond the outer marker if the visibility is below x or y) and procedures (go around if x or y fails before this point or that point). There were so many rules you almost forgot you were pulling off this amazing stunt. And it wasn't you anyway, it was you watching autopilots. So what equipment did the commuter airliners have tonight? Autopilots, for sure. (The Bonanza does not have one). But do they have WAAS GPS and glass PFD's like the Bonanza does? I'm not sure.

The bottom line is that 32R is not a CAT III runway, and the wind was 160/11, making it on (or just above) the tailwind limit for most airliners. So for one reason or another, autoland was probably not on.

Then there is the economics of it. The airline flight we were waiting for was a turn out of Chicago. Would it make economic sense to send the airplane down to try an approach? Probably not.

Why me?

Reflecting later on the approach, the first thing that came to mind was that the ATIS was reporting 200-foot ceiling and 3/4 mile visibility – exactly the limits for the LPV approach on 14L. What could they see from the tower? Were they helping me out? Luring me in?

Neither, of course. As Pilot in Command, the decision to land is mine. If they were calling the weather zero-zero and I landed, they would have to report me. That's paperwork, and if I had a compelling case for my decision, the paperwork wouldn't go anywhere. And anyway, in this business, if it is done right, there is no room for gotcha's. There is room only for teamwork.

And teamwork is what I got. The controllers cleared me for the approach as requested, and the tower cleared me to land on first contact, and then kept radio silence and watched on their radar. I could concentrate when I needed to. They broke the silence only when we had slowed almost to taxi speed, to confirm we were on the runway. ATC gets 100% on that one.

So I have made peace with it. I made my decisions as Pilot in Command, and our colleagues in Air Traffic Control supported us all the way. The airlines and aircraft manufacturers made their decisions, too, betting everything on autoland. Sometimes the little guy can do the job by hand when they can't.

Old and tired as I was, though, I couldn't have done it without the tiny diamond. For the next couple of days, the song keeps repeating in my head:

Diamond on the needle,

Diamond on the needle,

Diamonds on the soles of her shoes.

Pace, Paul Simon.

P.S. Oh, and here is Arcadia in Hangar 9 at FlightStar, after her work was done for the day.