September 27, 2014

The visibility is up to 4 miles, but the ceiling is still 400 feet. I can use Pincher Creek as a takeoff alternate. The wind is favouring runway 05 this morning – a great change from yesterday afternoon's 240/35. At 0945 local I take off into the ragged ceiling, cleared direct the VOR (YQL) and then on course, climb to 12,000 feet, call Edmonton Center through 6000 feet.

We reach 6000 at the VOR and are in the course reversal as we call. We break out between layers at 5000 and are on top of the next layer passing 10,500 feet. It looks like the high layer above will give way to blue as we move west. The OAT is hovering around zero, but as forecast there was no ice in the climb. Now it looks like the forecast will be right about the BC interior as well: little or no high cloud, and the stations either VFR or workable IFR in warm air. Here we are approaching Cranbrook (CYXC).

The OAT is hovering around zero, but as forecast there was no ice in the climb. Now it looks like the forecast will be right about the BC interior as well: little or no high cloud, and the stations either VFR or workable IFR in warm air. Here we are approaching Cranbrook (CYXC). Indeed, as we pass it is wide open.

Indeed, as we pass it is wide open. It is the gateway to the Rockies, as the view ahead confirms:

It is the gateway to the Rockies, as the view ahead confirms: Today's flight is another learning experience (as are all flights). I mentioned in my last post that my iPad overheated and shut down. I forgot to mention that just outside the FAWF on the approach to Lethbridge, the Loc and Glidepath (GPS) symbols disappeared and the GTN 650 announced that the approach was unavailable. Not enough satellites in view, I guess. The iPad (cooled and back up by now) was unperturbed. So we have the certificated avionics locking me out, and the Steve Jobs avionics acting cool.

Today's flight is another learning experience (as are all flights). I mentioned in my last post that my iPad overheated and shut down. I forgot to mention that just outside the FAWF on the approach to Lethbridge, the Loc and Glidepath (GPS) symbols disappeared and the GTN 650 announced that the approach was unavailable. Not enough satellites in view, I guess. The iPad (cooled and back up by now) was unperturbed. So we have the certificated avionics locking me out, and the Steve Jobs avionics acting cool.

Fortunately I was VMC and continued the approach. But it made me think even more about the many levels of instrumentation and avionics I am fortunate to have aboard, starting with the vacuum-driven Artificial Horizon and Turn and Bank. Then there are the pitot-static driven flight instruments and the legacy engine instruments. (By the way, Geoff Price and Bill Mehlen in CYQL diagnosed my legacy Manifold Pressure Gauge, which had developed the St. Vitus dance, swinging through 3 inches of indication. Broken bellows. Needs overhaul.)

Then I have the new glass panel avionics: the GTN 650, the Aspen 1000 Pro Primary Flight Display, and the EDM 830 engine parameters display, which includes a digital Manifold Pressure which is working perfectly. Finally, I have the Steve Jobs toolkit which includes the iPad and, fortunately today, the iPhone. As we now know, these can not only run their batteries down but also can overheat, and today the iPhone eventually does both. That is because for some reason my Satellite Weather receiver will not come up on my iPad. So near Cranbrook, eager for weather and radar updates, I use my backup – tethering the iPhone to the iPad and using the former's 3G. That works, but of course the iPhone needs more cooling now and is drawing more current. I'm going to add the iPhone USB cable to my cockpit toolkit, so if need be I can recharge the iPhone.

I have backups for backups in three or four categories of instruments, so any one failure doesn't result in a significant loss of information. But it makes me think again about how all this this technology, while ostensibly making our life easier, actually means we have to know a lot more: more about how each system works and what its limitations are.

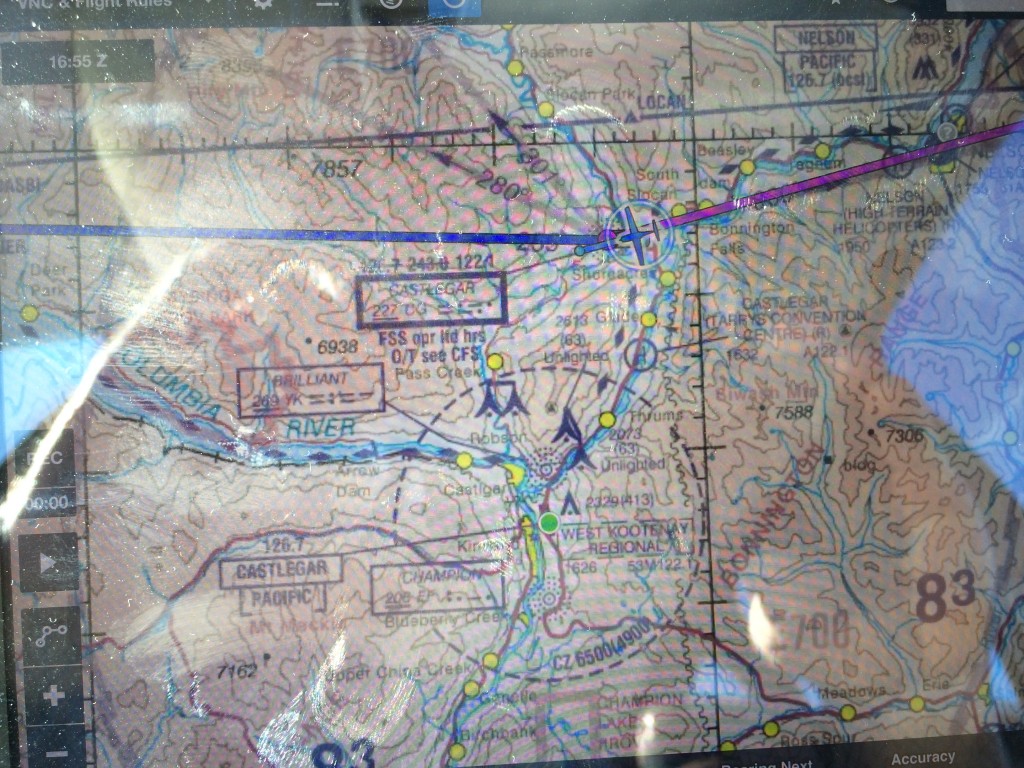

Now we are approaching Castlegar, flight planned over the beacon, CG. There's the airport, ahead of the left wing. The low-level cloud has mostly cleared out.

There's the airport, ahead of the left wing. The low-level cloud has mostly cleared out. I decide to bring up the Synthetic Vision mode on the Aspen PFD. It is a little disorienting at first because there is so much information. I start with SV2 mode, which shows me the Rockies only on the top half of the display. My eyes have to re-learn where to look, and I give them time to do so while the workload is low.

I decide to bring up the Synthetic Vision mode on the Aspen PFD. It is a little disorienting at first because there is so much information. I start with SV2 mode, which shows me the Rockies only on the top half of the display. My eyes have to re-learn where to look, and I give them time to do so while the workload is low. My thoughts drift back to the pioneers of 1939: how they had only my legacy instruments and the radio range. In cloud they had to visualize the rocks below. I am following Green One, the same airway they followed in 1939. I am flying at 12,000 feet for historical authenticity, but also because this is the only route with a 12,000-foot MEA (Minimum Enroute Altitude). The other airways are 14 thousand or higher.

My thoughts drift back to the pioneers of 1939: how they had only my legacy instruments and the radio range. In cloud they had to visualize the rocks below. I am following Green One, the same airway they followed in 1939. I am flying at 12,000 feet for historical authenticity, but also because this is the only route with a 12,000-foot MEA (Minimum Enroute Altitude). The other airways are 14 thousand or higher.

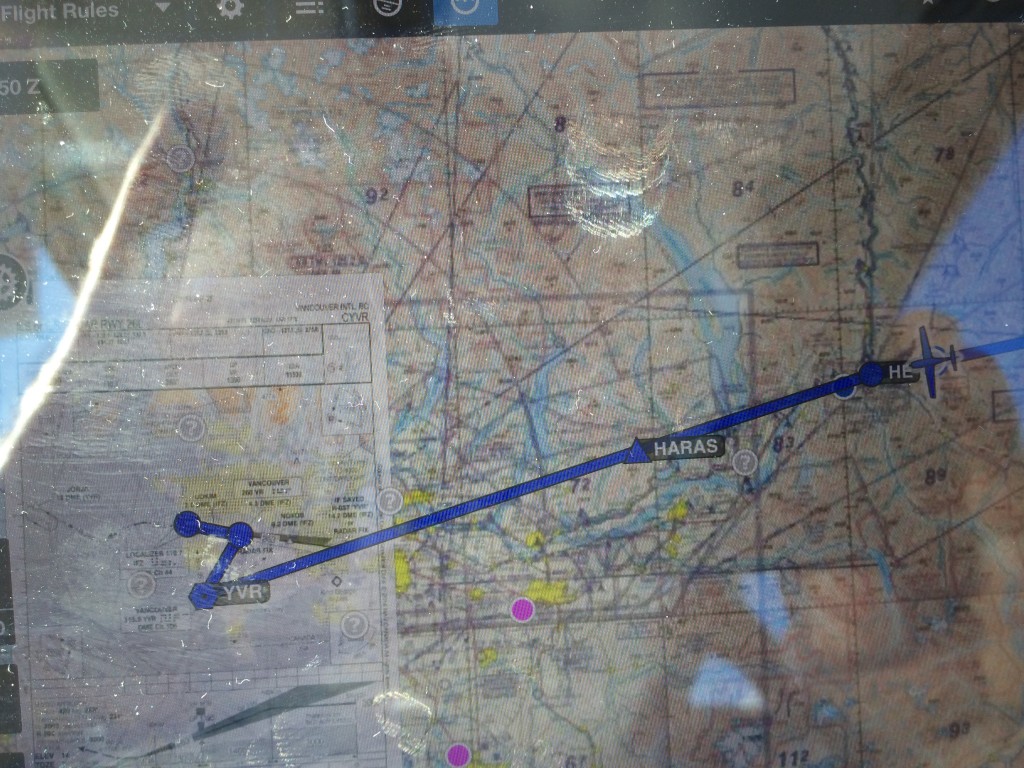

All this has taken co-operation with the controllers, who are eager to offer direct here or there to help you out. But when I explain what I am doing they are very helpful, both letting me stay on my flight planned route and sometimes relaying the information to the next controller. In the end I am allowed to stay on what was Green One until after Hope (HE). In fact, my re-clearance (another helpful controller) HE-HARAS-YVR keeps me right down the Fraser River. In the last hour I have become accustomed to the SV. Approaching Hope I switch to SV1, which is full-screen terrain. You can see the Fraser River Valley and the little white flag marking Hope airport – CYHE.

In the last hour I have become accustomed to the SV. Approaching Hope I switch to SV1, which is full-screen terrain. You can see the Fraser River Valley and the little white flag marking Hope airport – CYHE. Here is a closeup of the PFD at Hope, in a slight right turn.

Here is a closeup of the PFD at Hope, in a slight right turn. There is a good view of the Fraser River Valley – synthetic, of course. The view brings my thoughts back to the pioneers, and to the unfortunate pilots and passengers of TCA Flight 810, a North Star out of Vancouver, bound for Calgary on the stormy night of December 9, 1956. The weather was bad: their course took them into a trowal, a trough of warm air aloft associated with an occluded front, where warm moist air is being forced up over colder air. The moisture in the warm air condenses into cloud, rain, or snow, and occasionally into super-cooled water droplets which, when encountering a speeding aircraft wing, freeze instantly into glaze ice. In extreme conditions an aircraft can pick up its own weight in ice in a matter of minutes. That is a frightening experience, a true emergency.

There is a good view of the Fraser River Valley – synthetic, of course. The view brings my thoughts back to the pioneers, and to the unfortunate pilots and passengers of TCA Flight 810, a North Star out of Vancouver, bound for Calgary on the stormy night of December 9, 1956. The weather was bad: their course took them into a trowal, a trough of warm air aloft associated with an occluded front, where warm moist air is being forced up over colder air. The moisture in the warm air condenses into cloud, rain, or snow, and occasionally into super-cooled water droplets which, when encountering a speeding aircraft wing, freeze instantly into glaze ice. In extreme conditions an aircraft can pick up its own weight in ice in a matter of minutes. That is a frightening experience, a true emergency.

Flight 810 reported icing in the climb, and shortly thereafter a fire in the number two engine. The workload must have been tremendous. We will never know for sure exactly what happened that night, but we do know they had been on the airways Red 75 and Red 44, which are south of the Green One airway I am flying today. The MEA's are higher on the Red airways, but they make a shorter route to Calgary.

When they were forced to descend, both because of the shutdown engine and because of icing, they requested and received a clearance to return to Vancouver via Hope and Green 1. But they turned right. Why? Direct to Hope would have been a left turn. Here is a Google Earth shot of the terrain. You can see Slesse Mountain, and Hope to the north: We know they turned right because as it happened the flight was being tracked by radar from an installation just south of the border in Birch Bay, Washington. The radar operators were talking to neither Flight 810 nor its controllers in Vancouver, but they could see the flight as it turned right, describing an arc from east through south to west-south-west, and then tracking a good twelve miles south of Green 1 and the Fraser River Valley.

We know they turned right because as it happened the flight was being tracked by radar from an installation just south of the border in Birch Bay, Washington. The radar operators were talking to neither Flight 810 nor its controllers in Vancouver, but they could see the flight as it turned right, describing an arc from east through south to west-south-west, and then tracking a good twelve miles south of Green 1 and the Fraser River Valley.

I am thinking of them as I pass Hope. Here is what I see off my left wing at 12,000 feet: One of those peaks is Slesse Mountain, where the aircraft was found the next May, at an altitude of 7600 feet. I feel the loss. I am grateful to be here, over Hope, on this beautiful day. I wonder how they lost their situational awareness, but I am not critical or surprised. I imagine them in that terrible emergency, with all that pressure. Rest in peace.

One of those peaks is Slesse Mountain, where the aircraft was found the next May, at an altitude of 7600 feet. I feel the loss. I am grateful to be here, over Hope, on this beautiful day. I wonder how they lost their situational awareness, but I am not critical or surprised. I imagine them in that terrible emergency, with all that pressure. Rest in peace. Beautiful, isn't it? White clouds mixing with white snow on mountain peaks. But deadly if you don't know exactly where you are in three dimensions. I think of the importance in my trade of maintaining that mental picture, that situational awareness. I think of a recent study I heard about on the radio, where people known for their sense of direction were given a task of navigation through the small, twisty streets of London Soho. They did very well indeed. Then they tried a control group – still people with a good sense of direction, but supplied with a GPS. They did worse than the first group. Somehow the technology was shorting out their natural talent, as the crisis shorted out the situational awareness of the pilots of Flight 810. I think of what I have to do to survive, flying this airplane with all its modern systems. I have to understand the systems. I have to know their limitations, and be instantly aware if they are not telling me the truth. And I have to maintain my own mental picture with the highest possible accuracy.

Beautiful, isn't it? White clouds mixing with white snow on mountain peaks. But deadly if you don't know exactly where you are in three dimensions. I think of the importance in my trade of maintaining that mental picture, that situational awareness. I think of a recent study I heard about on the radio, where people known for their sense of direction were given a task of navigation through the small, twisty streets of London Soho. They did very well indeed. Then they tried a control group – still people with a good sense of direction, but supplied with a GPS. They did worse than the first group. Somehow the technology was shorting out their natural talent, as the crisis shorted out the situational awareness of the pilots of Flight 810. I think of what I have to do to survive, flying this airplane with all its modern systems. I have to understand the systems. I have to know their limitations, and be instantly aware if they are not telling me the truth. And I have to maintain my own mental picture with the highest possible accuracy. Now Vancouver is there under my nose. I am at 7000 feet, being vectored for an ILS to 26L as planned. There is a lot of traffic. Then the controller alerts me than 26 Left has closed. Remember a few posts ago, when I was on approach in Winnipeg and couldn't figure out how to change an approach in the GTN 650 once it was activated? Well, I went back to the book and it's dead simple. Just touch the name of the approach on the screen, and you have the option to change it.

Now Vancouver is there under my nose. I am at 7000 feet, being vectored for an ILS to 26L as planned. There is a lot of traffic. Then the controller alerts me than 26 Left has closed. Remember a few posts ago, when I was on approach in Winnipeg and couldn't figure out how to change an approach in the GTN 650 once it was activated? Well, I went back to the book and it's dead simple. Just touch the name of the approach on the screen, and you have the option to change it.

I do so now as he puts me on vectors for 26 Right. I remember the north side has different tower and ground frequencies from the south side. I have a standby CAP book beside me, open to CYVR ILS 26L. I flip it to 26R, and as I do I remember the tower frequency for the north side: 119.55. I remember because it's in my book, in Chapter Five. Otherwise I don't think I would have remembered. My last time in here was ten years ago.

Just as I relax a bit, having set up the ILS 26R frequency and making sure I have a glideslope again, the controller says, 26L is open again, can you switch back? Hey, no sweat. I've learned stuff since Winnipeg. Touch the approach name. Push the frequency knob to change the display to NAV. 110.7 for 26L is still in the standby window. Touch the top window, where 111.95 is displayed for 26R. The frequencies change position, 110.7 now active. Wait 15 seconds until I see the Morse ID appear: IFZ. Push the frequency knob again to change the display to COMM. Touch 119.55 to change to the standby, 118.7 for south tower. Check for glideslope on the PFD. Piece of cake!

I am on heading 180° at 5000 feet, crossing the final approaches for both of the 26's. B-777's are sliding east underneath me, on downwind for the right side. No need to tell me: he's going to dump me down as soon as he can and turn me east on a left downwind to 26L. I slow to gear speed and tell him what it is. He says, thanks for the heads up. I'm nearing the top of the cloud at 3000 feet. Then I'm IMC, intercepting the localizer just under the glideslope. Nice vector.

I love that moment when you break out of cloud and the runway is there. That's what instrument flying is all about. It's not that low today – I see the runway at about 1200 AGL. But it still makes me feel good.

A WestJet B-737 calls ready on 26L. Tower says hold short, traffic on 2-mile final, a Beech Bonanza. There is no one close behind me, so I concentrate on getting her slowed to 70 knots, her ideal speed with full flap. Then I ease below the glideslope so I can touch closer to the threshold. I want to turn off at the BRAVO taxiway, about 2000 feet down the 11,500-foot runway.

I do, and it's even a good landing. As I turn off I remember the last landing of my airline career, an A-321 on 24L in Montreal. Light winds, after a rain. Pilot's dream, because the wheels spin up slowly in the wet. Plenty of runway. Idle reverse and AutoBrake LOW. Smooth as landing in powder snow.

Sure know how to make a pilot feel good.